You will note the heavy use of foreshadowing in this report.

I was anxious and elated when I found out I’d be running the Barkley Marathons for the first time. From New Years through March, I chose training over social life or sleep whenever possible. A typical peak training week for me involved four days in a row of two hours after work hiking on a treadmill set to 15% grade wearing a 16 pound weight vest, followed by maybe a day of rest, then two days of 3-6 hours of hill repeats at 20-40% grade in my fully loaded race pack. My recovery day would be spent on the treadmill, starting next week’s progression.

I’d never trained harder for anything, but I knew deep down it almost certainly wouldn’t be enough, especially after a minor knee injury during a February fifty-miler cost me a couple key weeks. At the same time, I knew I had to put that aside and believe that everything would come together and lead me to somehow become the 15th ever Barkley Marathons 100 mile finisher. The worst result I could imagine was having a perfect run at my loop or loops only to stop short, unprepared physically, mentally, or logistically for all five.

The good news is that this did not happen.

I arrived in the greater Wartburg metropolitan area a couple days early to give myself time to do a bit of last minute shopping and check out the park. I took a nice walk up to the lookout tower Wednesday, thinking it would help me get the lay of the land. Thursday I wandered up Bird Mountain, then around and back down to camp on Quitter’s Road. After all, this would be the only time I’d ever let myself run that particular trail.

When I got back to camp from my motel at noon on Friday, it had gone from nearly empty and quiet to packed and bustling. Not only runners and their crew but the media, inspired no doubt by the recent release of an excellent documentary, had descended en masse. There may have only been 15-20 reporters and documentarians, but they were pretty noticeable at a race capped at 40 runners. I do not question their presence, though. Those who succeed at the Barkley deserve to have their achievements shouted to the world.

Much is made of the sharp humor surrounding Barkley’s rituals. Like the rituals themselves, it seems to serve a purpose. If everything at the campsite were treated as seriously as the race itself inevitably must be, the atmosphere would be insufferable.

Similarly, our race director lazarus lake seems to have become some sort of larger than life Dr. Frankenstein figure in the eyes of the internet and the press. I think he enjoys that, though, so I won’t try to disabuse you of the notion.

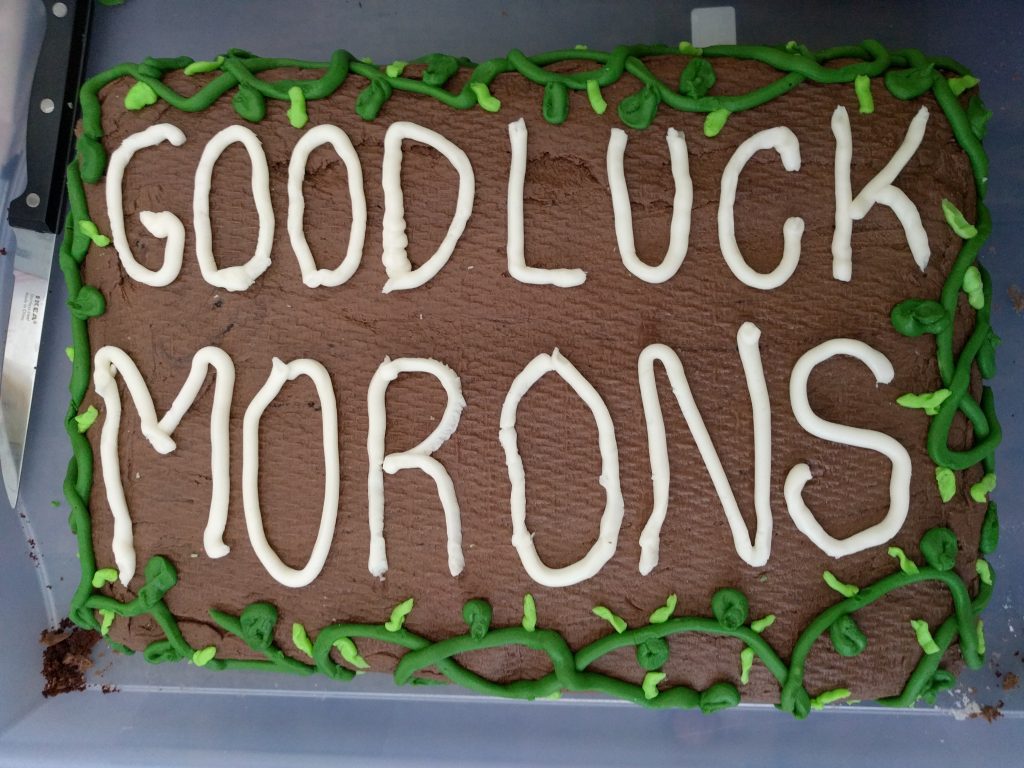

Some pre-race highlights: receiving our race bibs (“BARKLEY MARATHONS: WHERE DREAMS GO TO DIE”) and computer projections (“Starchy Grant: Will not run reverse loops for religious reasons”). Finding a braille card in the race packet with a verbal warning that one of the books would in fact be printed in braille[1]. A cake at the campfire potluck frosted in bright sawbriers and big, cheerful letters with “GOOD LUCK MORONS.”

It didn’t take long before everyone knew who this year’s human sacrifice was. Amidst all the teasing, I never saw anyone being anything but friendly and patient with this person. I won’t out them, but I will say they ended up doing just as well as a number of other virgins.

As night fell, I lay down in the back of my rental SUV for a fitful night’s sleep, knowing it could be anywhere from three to fifteen hours before the race began. If I poked my head up, I could see lights moving around up at HQ, but I didn’t know whether it was a camera crew shooting B-roll or laz getting ready to blow the conch.

I woke up in daylight terrified I’d somehow missed it, but as soon as I poked my head up I could see another competitor moving around camp unhurriedly. After taking my time eating and changing into race gear, I wandered up to campsite 12 to see what was going on.

The moment I got there, lazarus lake emerged through a veil of license plates into a throng of cameras and boom mics. He looked at his watch, raised a conch shell to his lips, and…

Nothing. He laughed and smoothed out his mustache. On the second blow, there was more of a “pfffft.” “I had this working really great yesterday,” he said, and tried again. Finally, on the third or fourth blow, it was official: B minus one hour.

The only problem was now I had nothing left to do to prepare. I think I was interviewed three times in that last hour. The first filmmaker asked me to “stretch or do whatever it is” I normally do. I don’t usually stretch before a race, but it felt nice. Someone from CNN set his camera up and pointed it at me just as I pulled out a stick of Chamois Butt’r and used it as advertised. Given a few extra minutes with nothing left to do but obsess over pack weight, I pulled out that one extra Clif bar I’d stuck in the night before. That still left me with about 5000 calories: a solid buffer to get me through up to maybe 18 hours in case something went wrong.

It was even one of the good Sierra Trail Mix flavor bars.

At 10:42am the starting cigarette was lit, and we were off. As I passed the gate I said, “Thanks, laz. See you soon.”

My lungs had some trouble warming up on the first climb, and I soon fell to near the back of the pack, puffing on my inhaler[2]. I was determined not to be scraped yet if I could help it: I’d heard many times the importance of sticking with a veteran during your first Barkley run. Of course, I’d also heard how important it is to pick the right veteran.

I stayed with a small group down through Fangorn Forest to book one, then started flying down Jacque Mate Hill after Jim Ball when I was tripped up by my own veteran mistake. Honestly, not tying my shoes tightly enough is a rookie move, but I seem to make it at every race. My ankles were flying all over the place on this steep off-trail descent, and I knew I couldn’t wait long to stop and retie. When I did, Jim was long gone, and I was on my own.

I missed the boundary marker at the bottom, although I probably wasn’t off by much. Stupidly, I decided to press on and make sure it wasn’t around the bend before backtracking. After a bit, John Kelly came running up to me from a seemingly impossible direction, saying he’d just lost half an hour looking for book two. I told him where I was coming from, he pointed out Jury Ridge, and then he was gone.

At this point, I had a quandary. I could follow John up Jury Ridge to the top, then descend on the right bearing to begin Hiram’s Vertical Smile. However, I was supposed to take the North Boundary Trail up to Jury Ridge before dropping down. If I followed John, I’d be cutting the course, but if I backtracked I could miss it again.

This is when I made the first of two disastrous decisions: I backtracked partway, then began making my way uphill on a bearing to intersect the NBT. I believe this was correct, except for one little problem: I’d never seen the Boundary Trail before. I knew it was described as a candy-ass trail, but I didn’t yet know how liberal laz might or might not be with that description. So when I hit an old overgrown jeep road, I didn’t know if that was it or not, but I put my compass to work finding the right line to drop off Jury Ridge.

This, of course, had been the second disastrous decision. As I had reached neither the North Boundary Trail nor the summit of Jury Ridge, this descent led me to the wrong valley, where I spent a long time following plausible but hopeless directions to the next book.

Finally I realized my mistake and tromped on back up the hill. This time when I hit the jeep road I tried to use it to cut over to the NBT, but after a while it petered out on a little spur. As I was standing there working out my move, I saw the last thing I expected: runners. After all that, there was still someone out there behind me.

I cut over a few hundred feet to join Rhonda-Marie and her guide runner Christian on the sweet, sweet North Boundary Trail. They weren’t much for conversation, though, as Christian was busy describing trail features and Rhonda-Marie was busy listening. So I pressed on.

From there I had only a little trouble dropping down from the right place on the right line to the right spot to find the next book. However, I’d spent five hours in all between books one and two. With a 13:20 total cutoff to find all 13 books and get back to camp and begin loop two, my race was over.

I might have come to Barkley hoping deep down that I could pull off at least a three-loop fun run finish, but I also came knowing that, in truth, the odds were against me, as easier versions of the course have thwarted hundreds of better runners than I over the years. In truth, as much as I might have hoped it, that had never been my primary goal. I showed up at Frozen Head State Park with one thing in mind above all: to run until I was told I was finished.

So I pressed on.

Somewhere after book three, I almost started to feel sorry for myself. Then I remembered what it said on my race bib, and I started laughing instead.

THE BARKLEY MARATHONS

WHERE DREAMS GO TO DIE

It was long dark by the time I go to the Garden Spot, and I’d gotten a bit turned around and wasn’t sure I was in the right place. Before long a couple of headlamps came up the road: Jared Campbell and Gary Robbins, lapping me. I’m used to it from Gary, at least. I think he’s lapped me four times in all at HURT. They pointed out the book I was pretty much standing next to, and we got our pages and ran together to the water jugs where I let them go ahead without me. Jared was one veteran I didn’t mind being scraped by.

A few minutes later I saw three new headlamps coming toward me. A trio of runners I hadn’t seen since book one asked if I could help them find Quitter’s Road. I declined, but invited them to join me in looking for the next book. They declined.

Route finding on Stallion Mountain at night wasn’t easy, but I was starting to get the hang of following both my compass and tracks of the runners ahead of me. At the bottom of the Barley Mouth descent, when I saw a pair of headlamps shining up from below me, I was confident enough to call out directions before continuing on, amazed to be passing anyone nearly twelve hours into what should have been at most a twelve-hour loop.

But then I thought better of it. If there was someone else out there having as much or more trouble than I was, I figured I should at least hang out long enough to make sure they were OK. And anyway, I was no longer in any real hurry. Maybe we could team up and avoid any more major navigation mistakes.

This was either the best or the worst decision I made all weekend. If I had to lay odds, I’d say both.

Brad was a long-time ultrarunner who had been out to Frozen Head for the Barkley Fall Classic, but he had no wilderness navigation experience and he was having trouble with the climbs after his trekking poles broke somewhere around book one. Kimberly, on the other hand, was having more and more trouble descending as the course beat on her legs, and she’d lost her map. She’d also run BFC and, more importantly, last year’s Barkley, where she’d made it as far as Garden Spot, just a mile or so back up the mountain as the butt slides.

Together we moved on to Leonard’s Buttslide, one of the most enjoyable hills on the course, with one of the most elusive book locations. As we were searching near the bottom, John Kelly lapped us, and the four of us briefly worked together to find it. We would not be able to keep up with him on the ascent, but as with Jared and Gary a few miles back, this was to be expected.

Bobcat Rock, Hiram’s Pool and Spa, and Stu’s Folly gave us no trouble, but something went wrong with our next descent and we didn’t see the highway after crossing the river. Many important Barkley landmarks such as streams and trees can be easily misinterpreted, but Highway 116 is not one of these. We had just returned from a failed bit of scouting in one direction or the other when we saw a new headlamp getting ready to cross the river toward us.

It was Andrew Thompson, a past Barkley finisher. Surely if anyone knew where he was going, it was A.T. We followed him east along the south bank before, without a moment’s hesitation, he appeared to dive up a monumental climb.

All he had said was that were too far left – or was it west? – and we’d have to cut back over on the road. I felt good that I was able to keep up this Barkley legend on a relentless 30%+ grade, but presumably his legs had worked harder to cover more distance in the same time I’d been using mine. When he paused to rest against a tree I pulled out my map and checked our bearing.

“I think we’re here,” I said, pointing out a short cut close to the road, and he nodded. I was not yet able to grasp the magnitude of our mistake. Eventually I stopped worrying about keeping up with A.T. and waited for Kim and Brad to catch up, and after confirming he hadn’t disappeared onto an invisible highway just over the next rise, we turned around and descended well over 500 feet back the way we came.

Later, much later, back in camp, we would learn that A.T. had led us up Little Hell, once most notorious of Barkley climbs. It has not been on course for at least ten years.

Back at the river, we started over on our search for the highway, more methodically this time. We could only possibly be too far west or too far east, so all we needed to do was try one direction, then the other. We went west along the riverbank until we found ourselves at an impassable gorge. Somehow, I still could not bring myself to lift my eyes from a small area on the map surrounding our target to locate the matching terrain, but it would not have mattered much. There was still nothing to do but try the east.

We reached a confluence, and before we could reorient ourselves we saw a new pair of headlamps and made our way over to them. It was Ty and Jason, cruising on loop two. We all headed south to where we knew the road would have to be, although we were still a ways off from where we wanted to meet it. Ty and Jason left us at the road, running down the shoulder to the turn-out we’d been looking for.

Once on the other side, attempting to navigate the new hill beyond Testicle Spectacle, we caught up with them again and spent some time fighting through laurel thickets together. After a time Ty asked us if we’d gotten our pages from the book five minutes back – not what we wanted to hear. We must have been so intent on catching up to them that we went right past book seven.

There was no shortage of confusion and frustration as we worked to find our way back over the hump of the ridge, looking for a faint trail of footprints to bring us back to the most vaguely described book on the course. If it hadn’t been for Mig and Dale coming up the ridge for their second loop and passing us just after the book, we might have had to descend all the way to Testicle Spectacle before we could usefully retrace our steps.

As we reached the top of the hill, day broke. This was both a relief and an immense disappointment. The light would help immensely, but the sun had just risen on day two of our first loop, and we were barely more than halfway done.

Kimberly’s legs were not up for the short, steep descent above Raw Dog Falls, and she let herself sit and slide her way down the forest floor. This seemed to be working OK, but after I reached the bottom and began to scout ahead, I heard her call for help. I didn’t realize what was happening at first, but when she called again I turned back to find a massive splinter a quarter-inch across sticking straight out of her lower leg.

“It won’t come out,” she said. I knelt down, counted to three, and pulled on it. She was right. I counted to three again and pulled again: my hand moved, but the splinter didn’t.

She didn’t seem happy with me at this point, but I apologized again, braced my other hand against her shin, and pulled hard and long. Finally, it popped out, and she had a new wound to join her brier scratches. We sat for a minute or two to recover, and then we pressed on.

We somehow missed Danger Dave’s Climbing Wall, which I regret, and while Brad split off to backtrack and find it, Kim and I chose to backtrack from where we were near the second highway crossing to book eight. Brad caught up soon after, but took his time following us back up to the highway and Pighead Creek. We were worried he was getting ready to give up. He thought we were getting ready to ditch him. Neither was the case.

As we climbed to the Prison Mine Trail, one of the easiest sections of the course to navigate, Kimberly nonetheless started to question our line. It didn’t seem right that we could be climbing so high, but still have Rat Jaw to come without a major descent in between. I turned back from my position in the lead and looked over her shoulder.

“This is right,” I said, “I promise. Look behind you.” Behind her was Jennilyn, coming around the corner as she cruised up the hill on her way to finish up a successful second loop. Once again, I found myself picking up speed as I fell in with a runner who was lapping us, and once again it’s hard to say how much I let her pull ahead so I could stick with the other two and how much she simply left me in the dust. She was clearly a woman on a mission to squeak it in under the cutoff, though, and I won’t pretend I would have kept up with her for long.

At long last we reached Rat Jaw, and I whooped with joy and all but sprinted up the hill. I might have been fifteen hours behind schedule, but I had been waiting for years to climb this fucker, and I would be damned if I wouldn’t enjoy every minute of it.

Up at the lookout tower, some of the water jugs were still frozen even in full daylight. When the other two arrived, we started a careful accounting of our remaining calories. Kim and I were running painfully low – we’d already been rationing for a few hours – but Brad still enough that he offered to hand off a Clif bar or two. Stranger still, as I was counting up my few remaining gels and chews, he pulled a baggie full of mac and cheese out of his pack, complete with plastic fork, and passed it around. I only had two bites, but it was among the best things I’ve ever eaten.

This is the memory I will carry most clearly from my first running of the Barkley Marathons: the lookout tower is, aside from the first and last miles of the loop, the easiest place on the course to quit and take an easy trail back to camp. In spite of everything, in spite of Kimberly’s beaten and bleeding legs, in spite of Brad’s broken poles and slow climbs, in spite of my dead dreams and frustrated hopes, none of us quit. None of us even said the word “quit.” After all, no one had told us we were finished.

And so we pressed on.

Descending Rat Jaw we had the new experience of getting lapped by runners on loop three, each of whom had the bonus fun of climbing Rat Jaw from the bottom. When we saw John Kelly down near the prison, I jokingly asked him if he’d gotten turned around – loop three is run in reverse, and getting even that far is an accomplishment most Barkers don’t manage. I guess his mind was still on our chance meeting by a creek so many hours before – he thanked me for getting him straightened out. Well, you’re welcome, John.

Traversing the drainage tunnel under the penitentiary was fantastic. That might be the only time you hear me say something positive about prisons in America, so soak it up.

On the other side, I decided to try climbing the chute to keep my feet dry. First I tossed my poles up onto the lawn above. Then I tried tossing my pack up, only to have it land on my head instead. Twice. Finally I got it up (no comments from the peanut gallery), and started using my long neglected rock climbing skills to chimney up. It seemed to be going well until my hamstring cramped in a non-negotiable fashion two thirds up. I got my feet wet.

Climbing The Bad Thing, I somehow spaced on the fact that we were headed for the Needle’s Eye at the top, and so forgot a piece of navigation advice that would have saved us a few minutes finding book 11, but it didn’t turn out too badly. Descending Zip Line, however, we (okay, mostly I) made a bad decision that put us on a parallel line. While not so disastrous as descending to the wrong valley, this is perhaps the most confusing place to be. Your compass tells you you’re doing everything right, but the course instructions no longer match up, and instead of simply running downhill to the next landmark you end up scouring every tree for a hidden book when you still have half a mile or more to go. Near the bottom we bumped into Dale on his third loop, who helped straighten us out.

I don’t know if Big Hell is the hardest climb on the course, but with all its false summits, making it the last climb on the course is… well, clearly it was the right decision.

Somewhere around half or two-thirds of the way, sitting to rest and let the others catch up, I cried out with joy, realizing only a moment too late I might have given them false hope that I’d spotted the summit. In fact, what I’d spotted was just as sweet: a second gel left over in my pack. I could eat now, and again at the summit. I sure missed solid food, though.

Kim sat down next to me and ate some of the Clif bar Brad had given her. I might have been visibly drooling. It was even one of the good Sierra Trail Mix flavor bars, too.

Further up the mountain, we spotted Jennilyn descending the next ridgeline over and called out to her. It looked like she was heading the wrong way altogether, getting off to a bad start on her reverse navigation. Worse yet, when she met up with us, she told us she didn’t have a headlamp packed for the loop. Kimberly handed hers off without hesitation.

Finally, after more false summits than I can count, I spotted it: the final book. I grabbed it, tore out my page, and burst into tears. I was simply overcome. I wasn’t happy. I wasn’t upset. I was just overcome with pure, unfiltered, unnamable emotion.

And then I ate my last gel, my very last literal ounce of food. We still had a few miles to go down the switchbacks to the campsite.

And so we pressed on.

Eventually we came out to parking area and a road. After more than 31 hours, it almost didn’t look right. Soon we were approaching the campsite, and we didn’t have any idea what kind of reception to expect, but before we got there Hiram, the many-year veteran who had scraped us so long ago, was high-fiving us out the window of his car. When we reached the bathhouse, in sight of our goal, we joined hands as we’d planned and started to run. With a small crowd that felt like a stadium around us cheering, we reached the yellow gate, and touched it, together.

Thirty-one hours, fifty-nine minutes, nine seconds. The slowest successful Barkley loop in history.

“Did we make the cut-off?” Brad asked.

laz, in turned, asked if we knew our pace. Officially, after all, we’d only covered 20 miles, although we guessed that in reality it was anywhere between 40 and 50 with up to 20,000 feet of climb.

Danger Dave played taps for us, one at a time, but before we left the gate I promised laz I’d had more fun Out There than anyone else that weekend. Maybe the five-loopers can contest this, but I still believe it to be true.

I try to learn something from every key race, and the lessons from this year’s Barkley will be stewing for years to come. Here, however, is one thing I learned for sure:

No matter how lost and hopeless I think I am, I can still be of use to someone else.

And I can still have a shitload of fun.

P.S.: If you’d rather hear me talk about this than read, I was interviewed for Ultrarunner Podcast. I don’t really advocate running badly as a route to stardom, but it sure beats not running at all.

1: Presumably in fairness to Rhonda-Marie, Barkley’s first blind runner.

2: I try to learn something from every key race. At Western States, I learned I have asthma.